This is my Three Summits Trek narrative. I did it with my son as an initiation right when he turned 16. It took place in Austria, Morocco and Greece in May and June (5 weeks). I provide the logistical details in three how-to posts. Those DIY posts include maps, costs, timing, requirements, photos and videos. This is a set of self-guided adventures on a shoestring.

Three Summits Trek Narrative Background

The concept behind the Three Summits Trek had started simply enough. On New Year’s day of this year Seth and I sat in a mountain cabin on the outskirts of Truckee, a small town on the northern shore of Lake Tahoe, California. A mighty blizzard had blown in over night and winds were reported to be in excess of 100 miles per hour on the peaks. So we sat around the cabin, literally brewing up hot chocolate and adventure stories to pass the day. I’d just finished reading Millman’s, The Way of the Peaceful Warrior, which concerns a young man who begins a spiritual journey of enlightenment. So it wasn’t a giant leap for me to asked Seth how he planned on marking his 16th year on this bright blue marble.

Over the past two years Seth and I had spent time together backpacking in Western Europe, bicycling across Florida, canoe camping in the Canadian wilderness, trail hiking the Southern Ontario Bruce Trail, and bush mountain biking. So Seth immediately knew where the conversation was going. He gave me a sly look and said, “I’d like to climb some mountains.” Chris Heuer, our cabin host, had been listening to our conversation with growing interest all this time and he proposed that we also film the entire project as a documentary. It didn’t seem like much of a technical leap to include digital video cameras and filming at this early stage of planning. We then began discussing possible mountain candidates in Europe and North Africa and settled on Grosser Priel in Austria, Toubkal in Morocco and Olympus in Greece.

A few weeks later I was back in sunny South Beach and began seriously looking into the possibility of the three summits. I began by searching the Internet for information about the mountains. I had no trouble finding details and climbing journals associated with Olympus and Toubkal. But Grosser Priel was more difficult due to the extraordinary number of mountains available for hiking in the Austrian Alps, but soon I had enough information to sketch out a plan. I wanted Seth’s adventure to be difficult enough to leave him with a life-long sense of accomplishment, but at the same time I didn’t want it to be so difficult that it would be unattainable. As for danger, I didn’t even consider it an issue since I felt that all dangers in nature could be reduced with serious planning, patience and experience. In this case we didn’t have much experience yet, but we did have ample patience and time for planning.

Over the next few months I approached a number of potential sponsors in order to get gear and training for the trip. Ed Arenas, of Arenas Casting in Miami made his facilities, equipment and connections available to us. Then Steve Kotter, of 2 Trails, provided us with climbing gear, Johnnie Hernandez gave us a three-month membership to the Larry North Fitness Center, Scott Hoey provided Seth with outdoor and weapons training, and Michael Siers, of the St Petersburg YMCA, spent hours with Seth on a climbing wall.

Seth finished his Junior year at Largo High School mid-May and immediately began a frantic session of serious socializing, rather than studying for his finals or packing for his departure in three days. I couldn’t really argue with his logic since he was a 16 year-old teen with normal social drives (i.e., friends and girls are the large objects of his universe, and parents are the remote background noise from outer space).

A week later we were in Switzerland. Our Eurorail passes covered the five contiguous countries we would be traveling to reach all three mountains (Switzerland was not included or economic reasons). We boarded a train and claimed our comfortable seats in an empty, air conditioned, compartment and settled back for a long sleepy ride. We were on a direct train to Vienna. We would simply exit the train at Wells, Austria and then catch a small one-car train that traveled between Wells and Grunau (our base camp for the Grosser Priel summit attempt).

Summit 1: Grosser Priel, Dead Mountains, Austria

The first objective was Großer Priel at 2,515 meters above the Adriatic, the highest mountain of the Totes Gebirge range, located in the Traunviertel region of Upper Austria. It ranks among the ultra prominent peaks of the Alps. There is a mountain hut (Welser) a half-day round-trip hike from the summit. It contains an emergency hut that is open all year. This was a two-day, one-night trek.

The first objective was Großer Priel at 2,515 meters above the Adriatic, the highest mountain of the Totes Gebirge range, located in the Traunviertel region of Upper Austria. It ranks among the ultra prominent peaks of the Alps. There is a mountain hut (Welser) a half-day round-trip hike from the summit. It contains an emergency hut that is open all year. This was a two-day, one-night trek.

Summit 2: Mt Toubkal, Atlas Mountains, Morocco

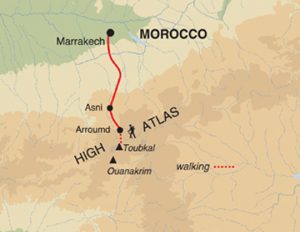

Our second objective of the summer’s summits was to scale Toubkul, 40 miles due south of Marracech. It is the highest and most accessible mountain massif of the Atlas range at 4,165m or 13,655 ft) and the highest of all North Africa. We predicted that this mountain would be the most difficult, both because of its isolated location in the heart of Morocco and because its trails were classified as “un-groomed,” what ever that meant. There is a refuge at 3,207m run by the French Alpine Club. This was a two-day, one-night trek.

Our second objective of the summer’s summits was to scale Toubkul, 40 miles due south of Marracech. It is the highest and most accessible mountain massif of the Atlas range at 4,165m or 13,655 ft) and the highest of all North Africa. We predicted that this mountain would be the most difficult, both because of its isolated location in the heart of Morocco and because its trails were classified as “un-groomed,” what ever that meant. There is a refuge at 3,207m run by the French Alpine Club. This was a two-day, one-night trek.

Summit 3: Mt Olympus, Greece

Our third objective was Mt Olympus, the highest mountain in Greece at 2,917m (or 9,570 ft). It’s a essentially a massive ridge, rising in rugged precipices to a broad snow-covered summit. According to Greek mythology, Olympus was the home of the Olympian gods.There is a refuge located near the summit that can be used as a high base camp. This was a three-day, two-night trek.

Our third objective was Mt Olympus, the highest mountain in Greece at 2,917m (or 9,570 ft). It’s a essentially a massive ridge, rising in rugged precipices to a broad snow-covered summit. According to Greek mythology, Olympus was the home of the Olympian gods.There is a refuge located near the summit that can be used as a high base camp. This was a three-day, two-night trek.

Click to watch the video trailer

| Jump to Toubkal | Jump to Olympus | Jump to Bottom |

Three Summits Trek Narrative: Summit 1

Grosser Priel, Dead Mountains, Austria

On an overcast Friday afternoon, in late May, our train pulled into Wells, Austria. We then headed for the village of Grunau and the Treehouse Hostel. We settled down to wait for our third member of the team, Toby, who I’d met the previous year while backpacking in Australia.

The following day we got a ride to our starting point, the Almataler Haus hostel at the trailhead of trail number 404 and 215 junction. We hoped to reach the summit, then spend the night at the Welsner hut and then return the following day.

It was quite cold when we stepped out of the van (12 Celsius or 50 Fahrenheit). We began hiking at a brisk pace to warm up. The trail was basically a gravel road that wound its way through a coniferous forest along a stream. In time the trail separated from the steam and turned into a comfortably groomed hiking trail.

Click to download detailed priel-route map.

Click to download detailed priel-route map.

After crossing a 100-foot wide dry riverbed, about an hour later, the forest began to clear and small scrub pines became abundant. At this point we noticed a few snow flurries. We excitedly began taking pictures and filming. We thought it was an interesting novelty, but didn’t think the snow would persist. After all, it the last week of May, well past the season of snow, even in these parts.

Soon the trail turned into a narrow rocky footpath that began to wind its way up the face of the mountain. The snow continued to fall and a thin coating of white covered the world around us. The ascent grew steadily steeper, the snow deeper, and the trail harder to follow. Our pace had slowed considerably. Another hour had passed and we were still climbing through a steep forest trail ankle deep in snow. We had been hiking for over two hours so we figured we should be near the hut at this stage.

After another half-hour of hiking things were defiantly looking questionable. The steadily falling snow had turned into a full on whiteout. The wind was gusting and large white wet flakes and fog had obliterated our view of the mountains above and below. Our visibility was limited to the surrounding fifty feet or so. Abruptly three people appeared on the trail ahead of us. They were descending quickly. They were wearing full winter gear and looked as though they had stepped out of an arctic expedition.

A conversation of sorts ensued, with hand gestures and mixed German and English. The gist of their message was that the mountain hut was closed and that we should head back. We smiled, thanked them and continued on our way towards the summit. This freak storm would probably blow itself out in a few hours and we could sleep in the shelter of the hut if it really was closed.

Shortly thereafter we came across a sign that pointed the direction to the Welser hut and indicated that it was still an hour away. We had been traveling for about three hours and were easily an hour behind schedule. Picking up the pace was impossible though. I tried cutting the trail and working my way up the face of a few glaciers but the effort of kicking foot holds into the icy snow, without an ice axe, was simply too much work. I had grown extremely tired by this point.

We continued on until the trees cleared abruptly and we were on the steep rocky face of the mountain. The trail wound back and forth along its face. In places steel guide cables were strung. We found the cables very cold and wet in the biting wind. I would only grab the cable if I absolutely had to. Each time my hand would come away feeling as if it had left a layer of skin behind.

Again the terrain changed. We were now hiking on rocky skree slopes and up and over small cliff faces. In places we had to scale steel ladders and then cross crevices on non-existent ledges. Perhaps there were ledges under the snow, but the trail was now invisible. We had difficulty finding the red paint splashes now. Our pace had slowed even more and the fourth hour slowly crept past.

Our circumstances had deteriorated completely. We were now in a full force blizzard with very few options. The trail had completely disappeared, visibility was down to twenty feet, and snow was gusting horizontally and was almost knee deep in places. The air had thinned markedly due to the altitude. I constantly stopped to pant uncontrollably. Seth and Toby weren’t in much better shape. The mountain had turned into a shear white slope. If one of us slipped we would simply slide off into oblivion. Toby was now on point, cutting footsteps into the slope, Seth was in the middle and I followed in the rear. Seth was having a great deal of trouble with his footing at this point. His boots constantly turned in the tracks causing him to fall to his knees and grab at the snowy slope with his bear hands. I caught up to him and had him rest while I dug out my spare socks. I gave them to him and instructed him to use them as gloves. I also gave him what was left of a walking stick I had made from a branch back when we were still in the forest. The stick helped him considerably and the socks seemed to brighten his spirits. He no longer looked as though he was on the brink of terror and on the verge of tumbling down the mountainside.

I then began to fall further and further behind. I had no stick, no gloves and the climb was taking its toll on me. I was stopping to pant every few minutes as the gap between Seth and I continued to get larger. I then heard an incredible sound. It sounded like the crack of heavy canvas sheets or a heavy tarp being whipped in the wind. I stopped to listen and dive for cover if it turned out to be an avalanche. It was then that I figured out what it was. The wind was whipping through the mountain gap to our left at such a velocity and with such power that it sounded as though giant sails were being whipped and cracked by a tempus. I grew nervous about my perilous position on the face of the exposed glacier, but was grateful that we were not in the gorge to our left. Little did I know that it would prove to be our next hurdle.

We’d been exposed to the weather for over four hours now. Obviously we had lost the trail and it was taking us much longer as we broke a new trail in the kneedeep snow. The blizzard had also grown so strong that Toby’s tracks were almost entirely obliterated by the time I walked in them. My hands had grown numb long ago and my pace a mechanical condition called survival. Up was the only available direction. The shelter of the hut had to be closer than the Almataler Haus four hours behind us.

Naturally when you think things can’t get any worse they always do. I rounded a massive outcrop and faced an open bowl. The wind was whipping down from a natural canyon between the two peaks above. Here the snow wasn’t as deep but the wind was so strong that it threatened to blow us clean off the face of the mountain.

Toby was well ahead on the open slope leaning into the wind almost parallel with the slope. He was making his way across the face to what appeared to be a rock gully on the opposite side. He stopped and gestured up at one point. I looked up and when the clouds parted for a moment I could make out what looked like a building. It had to be the hut. It was obvious at this point that it was every man for himself. I couldn’t keep up the pace and fell further and further behind. I soon lost sight of Toby in the rocks of the opposite slope, but pushed myself to keep Seth in sight. Eventually Seth crossed the bowl’s expanse one careful step after another. I could see that he was almost crawling on his hands and knees at this point. He had his head down and was simply trying to survive.

He made it to the rock gully as I reached the half way mark across the bowl. The wind was so cold and strong that I couldn’t go on any further. I sat down in the snow and listened to the wind whip and howl around me. In time I realized that I was no longer feeling the cold, or feeling much of anything else. This was not a good sign. My numb brain eventually coaxed me into standing so that I could at least film my surroundings before letting the elements have their way with me. Then I spotted Seth up among the rocks waiting for me.

I had no choice but to continue now. I couldn’t let him stand there waiting for me very much longer in this weather. He had been raised a Florida boy so this weather had to be magnitudes worse for him than it was for me, an ex-Canadian. I focused on my footing and took one step after another, head down and determined.

I finally reached the rocky gully and signaled to Seth to continue on. It turned out he had already determined that to be his wisest coarse. I saw him scurrying up above at the extreme limit of my visibility. Toby was nowhere to be seen. I continued on my way in short measured intervals picking a path randomly. There was no trace of a trail or footprints. The wind was scouring the rocks and blasting my face with ice crystals. I was using the bill of my baseball cap to protect my face from the sharp blowing ice, but had to keep one hand exposed on my head to keep the cap from blowing away.

About half way up the gully I spied Seth for the last time. He had briefly stopped at the crest of the bowl to look back at me and then disappeared over its lip. I mentally drifted off to a warmer and quieter place and continued up the trail slowly and mechanically. My extremities had long ago gone numb and my breathing demands kept me at a slow shuffling pace.

I finally reached the lip of the bowl and realized that I was only two hundred yards to the side of the hut. I gingerly picked my way through a maze of three-foot high pine bushes. I rounded the final turn and without a second’s delay leaped across a gap, yawing over an abyss, to reach the level ground of the hut.

Against the howl of the wind I forced the thick wooden door open and wedged myself into a small room with wall-to-wall shelves containing shoes and slippers. A fresh trail of snow indicated that Toby and Seth had continued through the door on the opposite wall. The wind closed the door behind me with a crash as I limped towards the next room.

Here I found some benches, stacked fire wood, a pile of dripping clothing, boots, and wet socks. I shed my outer wet layer as piles of snow fell from my shoulders, head and backpack. I followed the wet footprints up the stairs to a third and final room. This room had two layers of wall-to-wall bunks, blankets, a small table and an old fashion wood burning stove.

Seth was curled up in a ball on one of the beds shivering with all the blankets wrapped around him. Toby was hopping around wet and trying to crawl into his sleeping bag. I realized that the temperature in the hut was the same as the outside temperature (zero), but at least we were out of the wind. We now needed to desperately raise the temperature and dry our clothes (since we didn’t have any replacement dry clothing) if we were to survive the night.

I set about the task of making a fire in the tiny wood stove. A box next to the stove contained a number of logs, but certainly not enough for our needs. I focused on the immediate task of starting a fire with the limited kindling and my uncontrollable shivering. After a number of tries we got a small fire going. We then slowly worked the smallest of the available logs into the fire. Finally after about 20 minutes we had a reasonable fire going. Our prospects of survival had just increased exponentially.

We spent the remainder of the day comfortably eating our supply of baked beans and rice cake sandwiches while the room temperature increased to as much as 12 degrees Celsius (or 50 Fahrenheit). We hung up all our wet clothing on the available strings and hoped desperately that they would dry by morning. We then curled up in our sleeping bags with stacks of blankets pilled on top. We set Seth’s watch alarm to go off every two hours and then took turns putting a log in the stove when the alarm sounded. I had calculated that we had enough wood to last until morning if we used one log every two hours and that enough coals would remain in each cycle to light the next log. We didn’t have enough kindling to start another fire so keeping the fire going, while preserving the wood supply though the night were competing imperatives. I could only hope that the storm would blow itself out by dawn.

Gr. Priel Summit Day

We napped and shivered in turns though the remainder of the night as the wind continued to howl and shake the hut to its foundation. I awoke around 9am to random gusts and sunshine pouring through the window. The room was cold and the fire had long gone out. I roused boys and set about making a high-energy breakfast and we took our time getting ready to leave the comforts of the emergency hut.

We stepped out of the hut and into the brisk 16-degree (60 Fahrenheit) day at 11:10am. The snow around the hut was from knee to waist deep in places. We had all agreed that we would make a hard and fast push for the summit as long as the weather held. The sign at the hut said that the summit was only two hours away.

We stepped out of the hut and into the brisk 16-degree (60 Fahrenheit) day at 11:10am. The snow around the hut was from knee to waist deep in places. We had all agreed that we would make a hard and fast push for the summit as long as the weather held. The sign at the hut said that the summit was only two hours away.

I immediately began to doubt our plan. The trail began by skirting a shear cliff face and then crossing a bowl glacier to a cable climb that ended at a series of steep steel ladders. At no point did our feet touch a trail or solid ground. We were walking on the surface of icy snow and as the point I had to break the trail. A number of times my foot would break through to gaping cavities or twist and wedge among snow hidden boulders. Within a short time my ankles and shins were bruised and I was beginning to hobble on my right ankle. At no point did we spot any red pain trail marks.

Toby finally spotted a signpost on the opposite slope. They set off at an angle bisecting the open expanse while I followed. Half an hour later we were back on the trail and heading upward at a steadily increasing angle.

The next three hours were more of the same as we cut new trails across the faces of glaciers, over crests, through gullies, and around outcrops. We were either kicking footholds in icy snow or slogging through waist deep fresh powder. The going was so tedious and precarious that our ascent time doubled and at times I doubted we would even make it to the vicinity of the summit. Then around 2pm (three and a half hours after leaving the hut) the snow thinned and the mountain slope turned into an expanse of rubble on a large inverted bowl. At this point the footing became easy but our tired condition combined with the thin air made the going arduous. Toby and Seth continued on steadily as I fell further and further behind. And then when I thought I couldn’t go any further I heard Toby yell and looked up to see him gesturing. He had spied the summit at last.

With a final push I hobble the last fifty yards to reach a post from which the summit could be seen a few hundred yards to our east (across a snowy ridgeline). While the ridge looked scary it was at least almost horizontal. The red colored cross at the summit was extremely exposed and clouds kept whipping through the area to remind us that the weather changed quickly at altitude. I was done for the day and it was only 2:30 pm, four hours since we had left the hut. It had taken us twice as long as projected (again). We took pictures and filmed as quickly as we possible given the circumstances. We then un-graciously turned tail and began the long descent to the Hut and then our starting point, the Almataler Haus.

It would take us half the time to reach the Hut during the descent. We simply and recklessly hiked strait down most of the glaciers. Our concern was now to be clear of the mountain before nightfall. We reached the hut by 4:30pm and the Almataler Haus three and a half hours later at 8pm. We used the establishment’s phone to call the Treehouse and arrange for our pickup. By this time the sun had started to set, we were shivering and our clothes were soaked through.

Thirty minutes later Gerhard picked us up and asked if we had made it or if we had encountered any problems. I pointed out that we had run into a little blizzard and wondered if he had heard about it. He smiled and informed us that yesterday the proprietor of the Almataler Haus had told him that the mountain was closed due to deep snow and an approaching blizzard. I asked incredulously why he hadn’t shared the information with us the prior morning. Again he smiled and said that he knew we were tough and could make it. Toby, Seth and I looked at each other and fell silent and stared out the van window as Gerhard continued to happily babble about the history of the valley and pointed out local sights, including his childhood home where he grew up with his brother. To be polite I ask if his brother still lived in the valley. Gerhard fell silent and then got a strange look in his eyes and said that his brother was now dead. I expressed my condolences and asked how he had died. Gerhard replied proudly that his brother had been the best climber in the region, but had died in a late season mountain blizzard the prior year while hiking in the Dead Mountains. Seth, Toby and I stared at each other dumbfounded. The rest of the ride back to the Treehouse was in silence.

Summit 1 Photos

| Jump to Grosser Priel | Jump to Olympus | Jump to Top |

Three Summits Trek Narrative: Summit 2

Mt Toubkal, Atlas Mountains, Morocco

To reach Toubkul’s refuge, from Imlil village at the base of the mountain, a hiker need simply follow the river, at Imlil, upstream until reaching the structured camping area at 3,106 meters (starting on the east side, proceeding past the Berber village and then crossing over to the west side to find the trail that winds up the valley). In our case, around 12:30, we started from the Berber village of Douar on the west bank further up stream from Imlil, so we had to crisscross the stream in the wide river bed a few times until we reached the beginning of the trail on the west bank (about a kilometer upstream from the Berber village). This spot is recognizable by the beginning of a concrete aqueduct located about 100 meters beyond the trail’s beginning on the rivers bank.

The trail from here runs smoothly along the west side of the river with a gradual and constant increase in elevation. This section is well groomed and well traveled with only a few switchbacks until one reaches a crossover beside tent dwellings. The crossover can be seen from a distance because of a huge painted boulder that looks like a circus tent. This is also the first of a series of commercial ventures located between the village and the refuge.

The trail from here runs smoothly along the west side of the river with a gradual and constant increase in elevation. This section is well groomed and well traveled with only a few switchbacks until one reaches a crossover beside tent dwellings. The crossover can be seen from a distance because of a huge painted boulder that looks like a circus tent. This is also the first of a series of commercial ventures located between the village and the refuge.

We reached this crossover around 1:30 as our guide bid us to sit on the benches and relax. We were now hiking on the west side of the narrowing river valley at altitude. The trail had turned into a goat track that we could hike easily, but only in single file as it wound its way to the distant summits. Around 2:30 we rounded an outcrop with a narrow ledge overlooking the river and some distant streams falling from elevation. At this turn we were startled to find two Berber’s with an assortment of goods laid out under the rock overhang and a rubber hose running from a natural spring. Our guide asked us to sit and rest while he refilled his water bottle and the sales pitches began again.

The trail became narrower, wound more and swung into small side gorges beyond the outcrop. Over the next half hour we crossed three small creeks as the trail became progressively wetter and the landscape surprisingly more lush, with an abundance of liken and moss. By 3:00 we reached a strong tributary creek and sighted snow, for the first time, as the summits came into view. By 3:30 we sighted the refuge in the distance. It appeared as a stone building at the base of a waterfall with numerous tents on both sides of the river, which was now narrow fast creek more than a river. The sun was still shining but it was obvious that it would disappear behind one of the summits within a few hours. Clouds were already beginning to form above the refuge so we picked up our pace. The air temperature was 60 degrees Fahrenheit (15C). A comfortably brisk temperature for hiking at altitude.

Around 4:00 we reached the refuge, located at 3,145 meters (10,318 feet). I was a little winded, but felt quite strong at this altitude compared to our hike of Grosser Priel in Austria. Our guide disappeared while Seth and I hastily found a spot to setup camp. The temperature quickly dropped as setup our tarps and built a low rock wind shelter. We hadn’t bothered to inquire at the refuge about a bed for the night figuring that the night would be mild and that rock wind shelter would provide ample protections from the elements.

We had reached the refuge from Imlil in the planned four hours (taking into account the time spent taking tea in the Berber village) so we felt high with confidence and thin oxygen within the makeshift shelter. The proprietor of the refuge came over to visit us and ask us if we wanted to spend the night in comfortable beds. We declined his discounted offer of 75 Dh each (normally 120 per person for non-members) as he walked away shaking his head in disbelief. We should have been more attentive and considered the enquiry as a warning.

By 6:30 pm the camp grew quiet and fires began to go out as we became completely engulfed in clouds. We had started the day at 6 am and fell asleep easily to the braying of the pack mules wandering about the camp area. In less than an hour I awoke freezing cold and buffeted by a strong wind. Our tarp was ballooned like a parachute and in danger of being blown away. The wind had changed directions and was now blowing fiercely down the mountain face from the south.

I got out of my sleeping bag and built another rock wall on the opposite side to shelter us from the wind. I then added more rocks to hold down the tarp. It only needed to hold until morning, so cautiously, and very cold, I crawled under the tarp and buried myself in my sleeping bag.

I dozed in fits, but kept waking to the sounds of the wind, the tarp slapping and to my shivering. Finally the tarp began to tare, as I’d feared. Once again I crawled out and tried to reinforce our southern wall and snug down the tarp. Seth grumbled about my wall building abilities but didn’t move or offer a lending hand. Satisfied that we had a fifty-fifty chance of surviving the night, I crawled back into the structure and my sleeping bag. We were both terribly uncomfortable but stayed as still as possible for the rest of the night for fear of ripping the tarp.

Toubkal Summit Day

First light appeared around 6 AM as our guide showed up with a worried expression. He pointed at the fallen rocks and ripped tarp and simply said, “bad.” Seth was so cold that he had trouble opening his sleeping bag. I fished out my one long sleeve shirt and gave it to him to put on under his windbreaker and then gave him a chocolate bar to eat while I broke camp. He retreated to the shelter of a tall wall at the base of the refuge building and huddled in a shivering ball out of the wind while trying to eat the very frozen chocolate bar.

The guide reappeared as I finished and told us we were behind schedule and that we had to set off immediately. The guide simply setoff as we rushed to catch up with him.

My head was in considerable pain, I was still very cold, and I was starving as we set off uphill through the refuge at a fast pace. We walked upstream from the refuge to the base of the waterfall and crossed over via the remains of glacier that provided a natural bridge. We continued up the east side of the valley in packed snow and across a long open slope in the snow tracks of previous hikers. In places we climbed boulders, jumped snow gaps, or crossed open streams as we wound our way up and out of the valley and towards sunshine. The sky was cloudless and blue, but we were in the shadow of the surrounding summits so we continued to shiver for the next hour as we struggled to keep up with the guide. I felt so very weak from hunger or perhaps the lack of sleep. I was now lagging and struggling to keep up with the mountain goat of a guide and Seth. I constantly stopped to film as an excuse to rest and them simply stopped after ten to fifteen minute intervals that seemed to last forever. I gulped water at each break and panted like a winded dog. I simply couldn’t get enough water or air into my system, my head was killing me and I couldn’t get warm.

My head was in considerable pain, I was still very cold, and I was starving as we set off uphill through the refuge at a fast pace. We walked upstream from the refuge to the base of the waterfall and crossed over via the remains of glacier that provided a natural bridge. We continued up the east side of the valley in packed snow and across a long open slope in the snow tracks of previous hikers. In places we climbed boulders, jumped snow gaps, or crossed open streams as we wound our way up and out of the valley and towards sunshine. The sky was cloudless and blue, but we were in the shadow of the surrounding summits so we continued to shiver for the next hour as we struggled to keep up with the guide. I felt so very weak from hunger or perhaps the lack of sleep. I was now lagging and struggling to keep up with the mountain goat of a guide and Seth. I constantly stopped to film as an excuse to rest and them simply stopped after ten to fifteen minute intervals that seemed to last forever. I gulped water at each break and panted like a winded dog. I simply couldn’t get enough water or air into my system, my head was killing me and I couldn’t get warm.

Finally, around 7 am we crested the valley into sunshine and a trail without signs of snow. I sat in the sun for at least 20 minutes trying to catch my breath without success. I knew I was in trouble and was placing the venture in jeopardy. Seth seemed to be doing fine and was starting to warm up now that we had reached sunshine.

We set off again and I grew tired almost immediately. To keep me moving I chanted a steady mantra to myself, “just one more step.” Each step was a torment and we were only an hour from the refuge. We had at least three more hours to reach the summit. My head ached so much now that I just concentrated on each small step and let go of the time and the goal of the summit. My regular requests for a rest, every 15 minutes that seemed hours apart, caused the guide to grow concerned and he asked at each stop if I wanted to turn back. In each case I thought it over and conceded that I could go on at least one more time. But within a few minutes I was back to a pained and numbed state of panting and dragging my feet.

By 8 AM we had cleared the boulder-strewn stretch and were entering a skree-strewn valley with numerous steeply winding paths up the east mountain face. We took a very long and roundabout route that provided a more gradual ascent and surer footing. This reprieve didn’t help my condition since the air continued to get thinner. Finally around 9 AM we reached a point in the trail where we could look up at a structure that denoted the summit. I sat at this location for an extra long time, hoping to gain enough strength to push on to the summit. By this time a number of hikers had caught and passed us as I struggled with each step forward. We discussed our options and I considered letting the guide and Seth continue on their own to the summit, but in the end I determined to go on one more time at my own pace and reach it in my own time. I felt I had to be at the summit to film Seth’s accomplishment and also because these three summits had become my personal goal too.

We moved on for the final one-hour push to the summit. From this point the trail turned steep with switchbacks that wound steadily up. I could see the summit, but getting there wasn’t going to be a matter of taking a direct route. Time stretched as I concentrated on each step and taking long, slow and deep breathes, only to gasp like a fish out of water on each exhalation.

Around 10 AM the path curved around the last rock wall and the summit structure came into view up a long leisurely slope of loose stones. Seth and the guide continued on at a faster pace while I slowed even more. It felt like the last two hundred yards were going to be my last. About half way up the slope I stopped and began filming as Seth approached and touched Toubkul’s summit structure. I wanted to be there to film him as he reached the summit and I was, although about 100 yards back, rather than in front. I then made my way to the 4,167m high summit (13,672 feet) very slowly; knowing now that I would make it and that there was no need to hurry.

I reached the structure, touched it and then sat down completely spent. Seth handed me an orange, but I was too exhausted to peel it. I simply slumped, closed my eyes and panted the thin air as my head throbbed worse than any hangover I could ever remember. Seth peeled the orange and handed it to me. I ate it slowly then got up to take some pictures and film some more before returning to my slouched sitting position and falling fast asleep (or passing out).

At 10:30 AM the guide woke me and told me it was time to head back. I looked around at a surreal party scene. An alpine club had reached the summit and now at least thirty people were drinking champagne and smoking cigars. I asked the guide for another 15 minutes rest and passed out again. He woke me again almost instantly (or 15 minutes later to him). I struggled to my feet at 10:45 as the blood rushed from my head and I almost toppled over on the spot.

Breathing deeply and with concentration I began to walk down the slope and towards potentially thicker air. No matter how difficult it was to walk at the moment, I knew it wouldn’t get easier if I stayed, regardless of the time I took to rest. My breathing would get easier only if I continued in a downward direction. It was my only salvation and I knew it. The hike to the summit, from the refuge, had taken us four hours and I figured we could knock off at least an hour on the return.

The guide took us on a more direct route down the skree slope and at times we were scrambling out of control and in danger of rolling down the mountain. He kept prodding and cajoling us to pickup the pace. It seemed he was definitely in a hurry to make it back to his village and collect the remainder of his fee. My breathing became easier as we descended even though it remained difficult to keep the pace and my head continued to throb. By 11:45 we exited the skree valley and began down the steep boulder trail as my breathing continued improve. By 12:30 we reached the snow filled slopes and once again the guide picked a new and faster route. Around 1 PM we’d cleared the slopes and crossed the snowy ice bridge at the base of the falls above the refuge. I finally breathed a sigh of relief and felt the sensation of jubilation. We had done it. We had reached our second summit successfully.

I entered the refuge area spent, but breathing normally. I found the gear where I’d left it and fished out the first aid kit. I took two painkillers and an herbal energy pill, refilled my water bottle and then took a much-needed 30-minute rest (nap). Once again I opened my eyes to the guide’s impatient prodding. It was now 2 PM and we needed to be on our way if we intended to reach the base of the mountain and then Marrakech before nightfall. My headache had vanished and I felt fully recovered.

The hike back down the mountain to Imlil was done in record time as the guide set a perilous pace. He obviously considered his job complete and was looking forward to the remainder of his pay and to be home by dinnertime. We exited the trail at the aqueduct at 4:20 PM, and then reached Imlil (using the dirt road on the west side of the river this time) by 5:30 PM. We had a final glass of mint tea with our guide, paid him off and then set about haggling our taxi fare to Asni. We’d been informed that the last private bus from Asni to Marrakech left Asni at 4PM daily, so we had no choice but to take a taxi all the way back to town. We set the price at 120 Dh, for both Seth and I, to Marrakech and then settled down to wait for more passengers. Around 6 PM the taxi was filled with four additional passengers and we pulled out of the one horse town of Imlil for Marrakech via Asni.

By 8 PM we reached Marrakech’s Babb Roob, the taxi/bus collection point outside the city, found a petty-cab and returned to the Medina to collect our gear and head to the train station to catch the 9:15 PM night train back to Tanger.

Summit 2 Photos

| Jump to Grosser Priel | Jump to Toubkal | Jump to Top |

Three Summits Trek Narrative: Summit 3

Mt Olympus, Greece

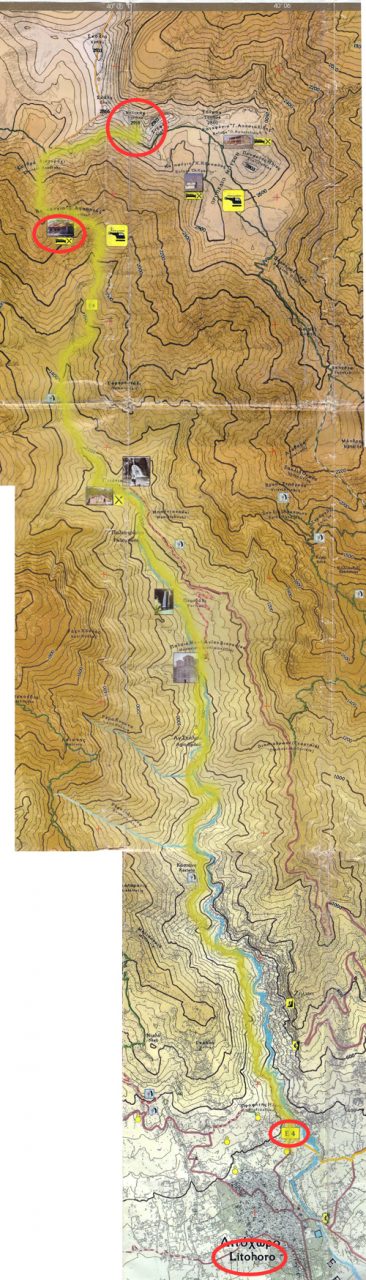

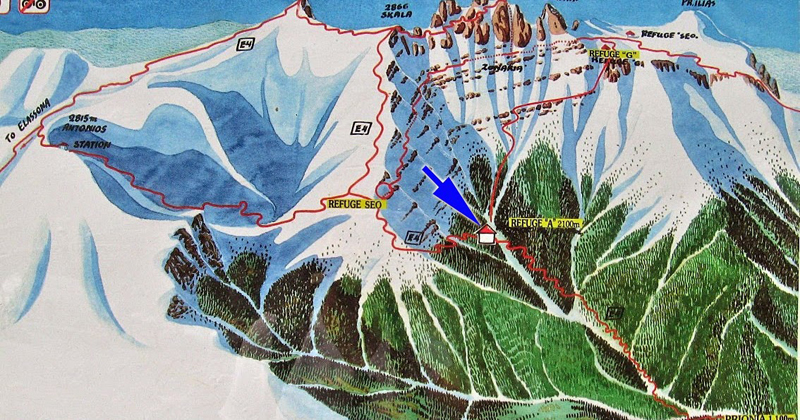

Click to download detailed olympus-route-large.jpg map.

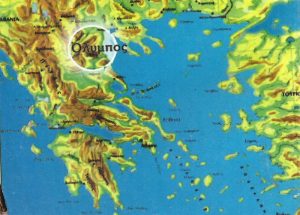

Mount Olympus (or more precisely, Mytikas) is located within Greece’s Olympus National Park, approximately 20 km inland from the Ionian Sea. Mount Olympus is the highest mountain in Greece, at an altitude of 2,918 meters. It is located in a cluster of peaks that are within easy walking distance of each other (Stefani at 2,907, skala at 2,866, and Skoio at 2,911). The national park is approximately one hour’s train ride south of Thessalonica, the second largest city in Greece. The closest town and the location of the best trailheads is Litohoro, which can be reached by hourly buses from Katarini, located on the main Athens-Thessalonica rail line.

Seth and I had a number of trailhead options when we reached Litohoro, at an altitude of 400 meters and being only five km from the sea. Our first objective was the Prionia information center and restaurant, altitude 1,100 meters. We could hike 4-6 hours through the forest at the base of the mountains, following the European E4 trail, or we could simply take a taxi along an 18 km winding road on the north side of the valley. Actually there are two trails leading out of Litohoro, the E4 trail (exiting the town to the west) follows the river through the gorge to Prionia and then continues to the cluster of Olympus mountain summits. The other trail exits the town further south, bypassing Prionia, and merges with the E4 trail near the summits. This second trail, classified as scenic for its vistas, works its way around to the upper crest of the gorge and valleys, is much longer than the E4, and has considerably fewer places to find water.

Seth and I had a number of trailhead options when we reached Litohoro, at an altitude of 400 meters and being only five km from the sea. Our first objective was the Prionia information center and restaurant, altitude 1,100 meters. We could hike 4-6 hours through the forest at the base of the mountains, following the European E4 trail, or we could simply take a taxi along an 18 km winding road on the north side of the valley. Actually there are two trails leading out of Litohoro, the E4 trail (exiting the town to the west) follows the river through the gorge to Prionia and then continues to the cluster of Olympus mountain summits. The other trail exits the town further south, bypassing Prionia, and merges with the E4 trail near the summits. This second trail, classified as scenic for its vistas, works its way around to the upper crest of the gorge and valleys, is much longer than the E4, and has considerably fewer places to find water.

It was 2:30 pm by the time we had restocked our supplies, organized our gear, and were ready to setoff from town. We did our repacking and organizing in the shade of an abandoned church structure located along the Enippeas River, by the alpine climbing and rescue building. We returned to town (to the south side of the river) and followed the blue signs that pointed to the Canyon. We continued westward through town, always within a short distance from the river until we reached a dead end road with the Pension Olympus Restaurant at its terminus. A natural spring is located at its gates and the E4 trail passes through the parking area next to the restaurant. We filled our water bottles from the cold spring, talked to the restaurant owner for a bit and then setoff on the well-groomed trail at 3:00 pm.

The trail here is well traveled but a bit confusing. The marked E4 trail follows the course of an aqueduct only a short distance and then switches back on itself, at the junction of a tiny trickling creek, and then winds up the face of the gorge. The other trail, beyond the switchback, continues to follow the aqueduct and terminates at a small dam and structure on the riverbank (well below the E4 trail). The hiker that misses the switchback has no choice but to retrace his steps from this dam and find the switchback or attempt to climb up the face of the gorge to join the trail high above.

The trail here is well traveled but a bit confusing. The marked E4 trail follows the course of an aqueduct only a short distance and then switches back on itself, at the junction of a tiny trickling creek, and then winds up the face of the gorge. The other trail, beyond the switchback, continues to follow the aqueduct and terminates at a small dam and structure on the riverbank (well below the E4 trail). The hiker that misses the switchback has no choice but to retrace his steps from this dam and find the switchback or attempt to climb up the face of the gorge to join the trail high above.

Following the correct path we came to a “Y” in the trail. Again we paid particular attention and searched for the distinctive trail marks. We turned to the right, the logical direction upstream and further into the gorge, rather than to the left. By this time the sun was shining directly overhead and the temperature was hovering around 30 C in the shade. We were in a constant state of sweat and panting, but after our prior exertions in Austria and Morocco, I felt fit enough to enjoy this vigorous hike. Plus this would be our last summit and I wanted to savor the experience. Seth, on the other hand, seemed eager to get it over with.

We were now hiking in a rugged forest of holm and kermes oaks, Greek strawberry, ash, maple, and turpentine trees. The trail followed the eccentricities of the natural gorges and washes created by the river. At one moment we would be walking along the river and then turn to follow the trail in a grueling upward and winding direction, panting as we crested a spine of rocks in direct sunshine. We would then start a long winding decent within the shade of the damp forest only to return to the riverbed a short distance upstream. This meandering approach would consume many hours and many km to cover a relatively short distance, as the crow flies.

We refilled our water bottles at every spring and at the river each time we approached its banks. We had learned through bitter experience that we should never take water for granted on our outdoor adventures. We had a good map and were planning each stage carefully. Then we met a hiker who had no map and was in obvious need of water. We let him drink his fill from our remaining bottle with worried expressions. We reached our next watering point with less than half a liter remaining.

Around 5:00 pm we spotted a side trail leading down a gravel embankment to a natural camping area and swimming hole. We had a cold snack, took a swim and rested in the shade while observing the numerous insect, fish, reptile, and crustacean activities in the frigid mountain water.

By 5:30 pm we gave up on the natural spectacle and repacked and made off at a comfortable walk. We reached Kastana spring by 6:40 pm and started to pickup our pace a little. We had been hiking very casually most of the day due to the heat and our prior poor night’s sleep. I knew that we could reach Prionia by 8 pm if we hustled, but I didn’t actually want to reach it. Camping within the Olympus National Park is not really permitted, per the posted signs. However, camping does take place, especially at sites of abandoned homes near the Dionisiou Monastery. Our first objective was the natural camp areas located a short distance before the Agio Spileo cave temple. This small temple is built into the rock face within a large natural cave created by a spring. Our second, but much further objective, was the open grassy area near a dirt road leading from the Dionisiou Monastery. We reached our first objective, just shy of the spring temple, around 7:00 pm and found a young couple camped there. Rather than disturb their solitude and intimacy, we moved on towards our second objective at a quickened pace. It would be dark within the rim of the gorge by 8:30 pm and we were still a ways from reaching the second objective. I began scouting the areas along the trail, as we hiked, in search of a potential alternate campsite.

We reached the cave spring and temple by 7:30 pm and I considered camping there for the night, but ultimately felt it was too damp a location, and perhaps it might be viewed as a bit sacrilegious. Before abandoning the site as a potential camp area, I dumped my gear, while Seth rested, and set off at a fast walk along the trail to see if it opened up into a flat area or turned back down towards the river. Since passing the previous camp area we had been hiking along a thin trail carved into the side of the gorge, at altitude or in thickets to dense for camping. Ten minutes of hiking and the trail began a steady downhill descent. I then returned to the spring to collect Seth and my gear. At this late stage we setout a bit apprehensive. We were quickly running out of daylight.

The trail soon wound down to the riverbank and flat open areas began to appear. We scouted as we hiked and considered a few likely spots until I realized that we had almost reached our second objective. By 8:15 pm we reached the footbridge that lead to the dirt road and open grass flats along the river near the monastery. I knew that this area was well traveled since it could be reached road, but it was also an excellent natural camping and swimming area. We setup camp quickly as a group of fellow campers returned from a chilly swim.

We had a cold dinner and then crawled into our tent by 8:45 pm for a much needed night of comfortable sleep. As we lay in the tent laughing and telling stories the mountain gods began to debate our fortunes with loud rumblings and flashes. The day had been a beautiful sunny blue-sky day and I was telling Seth that I didn’t think it would rain, even though legends told of frequent nightly thunderstorms, just as the skies opened up. We lay quietly, munching on sweets, while the gods put on a light and sound show and the cold drops echoed off the tent walls. I don’t know how long the rain lasted since I fell asleep almost instantly.

Day 2

We woke to the noisy racket of the local birds around 7:45 am. I stuck my head out of the already hot tent to find that the sky was a vivid blue and cloudless. The gods must have agreed that we deserved a reprieve from nature’s wrath. Seth and I had had more than our share of cold spells in Austria and Morocco. Some good weather would be a pleasant change.

We had a comfortable breakfast at the river, washed up and then broke camp reluctantly. Finally, around 9:40 am we started along the path to Prionia. For the next hour we walked through abandoned pastures and dwellings. Who owned the land in this area is questionable. I’m not sure if it is part of the national park, especially since we encountered a camper who had been squatting at this location without problems for the past six weeks. In any event, it is a natural location for habitation with its flower filled meadows, and obvious campsites.

We had a comfortable breakfast at the river, washed up and then broke camp reluctantly. Finally, around 9:40 am we started along the path to Prionia. For the next hour we walked through abandoned pastures and dwellings. Who owned the land in this area is questionable. I’m not sure if it is part of the national park, especially since we encountered a camper who had been squatting at this location without problems for the past six weeks. In any event, it is a natural location for habitation with its flower filled meadows, and obvious campsites.

By 10:30 am the trail re-entered the forested tracks and once again wound its way back and forth across the river and gorge walls. Here the forest had a distinctively different makeup and feel from that of the previous day; it felt very much like a Canadian, Ontario pine forest. It now consisted of huge tracts of black pine. Smaller groups of fir, beech, elm, hazel, and cornelian cherry trees also abound; the occasional clearings contained many mossy plants. The ravines and gullies were covered in oriental plane, gray sallow, alder wood, and riparian vegetation.

At 11:00 am we crossed the last of the frequent ornamental wooden bridges to reach the Prionia parking area and information center. We dumped our packs and entered the tiny restaurant for a touch of civilization. The interior contained rows of pick nick tables and old sawmill paraphernalia. One hundred years ago this water-powered mill cut the local pine into lumber that was carried down the, now paved, road by mules to local villages. The day’s menu consisted of bean soup, Greek salad, or fried sausages. They also offered several liquid refreshments housed in a box cooled by the river’s frigid water. Seth and I ordered one of each item and sat back to gobbled our second breakfast or early lunch like ducks.

At 11:30 am we exited the restaurant reluctantly. Our host had given us an interesting brochure about the history and wildlife of the area and bid us well. I think he felt hospitable to us in gratitude for our patronage and a bit guilty because the toilets weren’t working (toilets are always appreciated by campers who have had to make due with natures lack of facilities).

We filled our water bottles on last time, walked through the parking lot, and then up a gravel road that terminated at the trail. We crossed the last of the picturesque bridges and then began a steady uphill hike away from the river. This part of the trail would continue painfully uphill for the next two and a half hours. I knew that two hours of uphill hiking, in the sun and at altitude, should not be too much of an issue, but hot tiring work is exhausting no matter how fit you are. The trail wound its way back and forth along the diminishing valley and out of site of the river.

The vegetation changed from tall pines to the rare stunted Pinus Heldreichii pine and shrubs. Shade began to become a commodity sought after. We were once again consuming water at a steady pace. About an hour along the trail we stopped to catch our breath as a group of about ten Latvian hikers passed us. Spurred on by this competition we continued to leapfrog each other at intervals along the trail. We all panted and sweated profusely while gulping down our quickly diminishing water supplies (which incidentally made our loads lighter). That final hour to Refuge A (Agapitos) seemed to take far too long and consumed way too much energy. Perhaps it was due to the rich bean soup, salad, and sausage mix that was churning around in our bellies. Whatever the cause, the results were a pair of very tired hikers when Refuge A was reached at 3:00 pm.

We had originally planned on resting at the refuge and then continuing on to the summit and then returning to the refuge (or one of the others on the other side of the summit) for the evening, but now reconsidered. It was almost 4:00 pm by the time we finished snacking and lounging on the sunny benches in the courtyard and it was obvious neither of us wanted to leave. Further, we were informed that clouds obscure the summit on most late afternoons and evening storms are frequent. With this (or any excuse really) we determined to spend the night at the refuge and set out the following day. We could make the summit and return within five hours. We could then rest and return to Prionia by late afternoon. We could then try to catch a ride back to down with the departing tourists that drive up to Prionia for the day. With this firm plan in hand we settled down to relaxing. Seth fell ill from some dubiously titled canned food by the name of “Breakfast Meat”, closing the deal on spending the night. After checking our gear, the cameras and our minimal food stocks we attempted to get some rest in the cold refuge.

By 8:00 pm Seth was awake and hungry again (hunger seemed to be his constant companion). Dinner at the refuge became a pricey affair given Seth’s appetite. After dinner, we sat in the warm dining room, near the fireplace, and confirmed the next day’s plans before retiring for night. That evening Seth discovered that “lights-out” really meant lights-out. When he got up twice to visit the basement bathroom (hole in floor) in the dead of night he found that none of the lights worked. He had to find his way out of the room, along a corridor, down stairs, and into a closet with a hole in the floor, without any lights. He then had to reverse the process to find his way back to his bunk. The next morning I laughed and informed him that I had left the flashlight at the foot of his bed in case one of us had to attend to a call of nature.

Olympus Summit Day

The next morning I was up and about by 6:30 am and in good form. My night’s sleep was wonderful even though the unheated dorm room had been absolutely freezing. I had taken the precaution of stacking a good number of blankets over my sleeping bag, and then a few more at my feet as backup. This morning the room was not much warmer, even thought he sun was shining brightly in an unhindered sky. I noticed that a few hikers had already left as I nudged Seth back to reality. I sensed that he could sleep for the rest of the day if left to his own devices, but he was eager to finish the long journey. He was naturally grumpy (as always prior to at least two meals), while I was excited and hyper.

Compared to the morning of our Toubkul ascent, I was at the other extreme of the spectrum of health and good spirits. The proprietor of the hut had told us the previous day that we could leave our gear in the hall storage area while we made the ascent and then return for it later in the day. This would make our ascent even easier. I packed a day bag and the camera gear while Seth got started. We then shared a comfortable breakfast before setting out at 8:00 am.

We followed the trail out of the hut area and up the steep mountain face as it wound its way in a slow zigzag pattern though ever shorter and fewer stunted pines and coarse mountain grasses and mosses. Within half an hour we were completely beyond the extremes of plant life and hiking in ruble and boulders. By 9:00 am we came to a confusing trail crossing. At this point, high up on the side of a long sloping expanse, the trail continued strait with a new trail heading off to our right. Our map showed a location that could be this spot, but on the map the trail crossed from left to right, not simply to the right. Some faded paint markings appeared to indicate that Skala and Skoio lay directly ahead, while Mykitas lay along the right-hand trail.

We sat at this spot and talked over our options. We guessed that the trail ahead would lead to the backside of the mountain range, and hence Skala and Skoio, while the right trail lead to the face of Mykitas and then either directly up to the summit (the hard way) or to the refuges to the north. As for the missing left trunk of the junction, we assumed that it was a short ways back and that we had simply missed it. If these guesses were correct then the crossing trail was the scenic green trail marked on our map that originated south of the trailhead we took in Litohoro. Our day’s schedule was tight if we planned on making it to the summit and then returning to Litohoro, so we had to commit to one route or the other. We opted for the trail to the right since we knew we would have to go right at some point in order to approach the summit from the much harder and steeper face.

The trail took us to the crest of the slope that we had been traversing and then along a very vast open and windy slope on the open face of Mykitas. We were either sweating from the exertion and sunshine or freezing when the cold wind found us exposed along the half-meter wide icy skree trail. This open area along a face of the mountain was one continuous slope with intermittent melting glaciers. One slip and you were bound to tumble a very long way down the mountain until the fall was abruptly stopped by a boulder or the trees a thousand meters below.

This long frontal traverse made very little upward progress. I kept looking up wondering where a possible trail up would be found. No sign of an upward trail seemed evident. By 10:30 am we found metal sign leaning precariously against a rock. It was pointing strait up the face of the mountain. Whether it really pointed up was a question we discussed since it was not attached to anything. Perhaps it was simply meant to point along the horizontal trail, but had been turned sideways by a comedic hiker. Seth pondered the shear vertical face while I continued on another 200 meters to what appeared to be another sign. The second sign was actually a radiophone hard wired to a mountain rescue station. At this point I also noticed trail markings going up the face of the cliff and to the left, over and above where Seth was still standing. So the sign did indeed point upwards and confirmed the green trail marking on our map.

I pointed up and nodded my approval. Seth smiled and eagerly began to ascend the face hand over hand, crawling and hauling at places, stepping across crevices at others and simply climbing at all times. This was a straight up trail. I started from the radiophone and made my way up and over. We joined up after a time and then took turns leading and following in short twenty-meter intervals. It was demanding and attentive work. Even while resting the mountain gave no comfortable ledges along this route. We had to hold on at all times or a guest of wind might simply nudge us off balance and down to our demise. There was no question that a fall from this face would be fatal. We panted, filmed, climbed, took pictures and rested in turn as we slowly made progress upward. No real trail existed along this route, but a suggested path had been marked by paint splashes and in some places anchor points were evident for roped belay ascents. Once again we had opted to leave the climbing gear behind due to weight considerations. Weight was a huge issue since we were our own Sherpas, hikers, cameramen and climbers.

By 11:30 we finally approached what appeared to be final fold that might lead to the summit. I crawled to the edge and looked over into a void of at least a thousand meters. That was not the direction to take in a snowstorm or fog. I was grateful for the clear skies and sunshine as I remembered the fog and snow that had engulfed us when we summated Grossner in Astria. I turned to the left and continued up the face. The surface here had changed from shear cliff and confused and scared rock face to a large jumble of surreal boulders. We easily climbed and hopped up this last obstical and emerged into an open, but rocky area five meters square. In the center stood a metal Greek flag, a concrete mantle and a guest book. We had made it. Standing on the summit we could see in 360 degrees. The back face of the mountain was a smooth moonscape of gentle slopes, brown stones and dirt. We could clearly see the summits of the nearby sister mountains. They were each easily accessible via clearly marked trails that lead from one summit to the other. Only to Mykitas presented a formidable challenge to the hiker (even from the backside which we would take for the descent).

We stayed on the summit for over half an hour to savor the victory over the elements and our personal limitations. We then set off to visit Mykitas’ neighboring summit of Skala (2,866). Seth then felt inspired enough (or delirious from lack of oxygen) to run the four km circuit to Skoio (2,911). I simply sat content on Skala and watched him turn into a tiny dot on the next summit before returning and then heading back down to the world at speed. Gravity and high spirits made the descent swift and a bit perilous at times. We reached the refuge by 1:30 pm and Prionia by 6:00 pm. We then sat and hitched a ride back to Litohoro from a returning tourist.

We had made it to our final summit in good health and good spirits. Olympus, while not the highest of our three summits adventure, was in fact the most technically challenging and picturesque. The seat of the gods was indeed a climatic and grand conclusion to our five weeks of toil.

| Jump to Grosser Priel | Jump to Toubkal | Jump to Top |

If you read this far you deserve to see more. This is the 9 minute Combined version.

Check out the 3 minute Adventure version.

Click the big yellow button to become a patron!

Link back to DIY Summit 1

Link back to DIY Summit 2

Link back to DIY Summit 3

Home